The History of Papier-Mâché

The Origins

From Beijing to Venice, from Mexico to Kashmir, modeled paper has crossed cultures and centuries. Traveling the world reveals countless traditions.

In China, during festivals, paper dragons ripple between drums and bursts of laughter, carrying with them the echo of ancient legends. The streets are adorned in red and gold — the colors of fortune — while the dragon’s sinuous movement links heaven and earth in a dance of light and hope. Here, papier-mâché is a symbol of good fortune, of vital energy in perpetual renewal. Each hand-shaped figure holds within it the patience of artisans and the poetry of gestures passed down through time — a silent dialogue between humankind, matter, and benevolent spirits.

In India

In the temples of Kashmir, tiny paper deities wait silently for prayers, as delicate as a breath. The hands that shape them move slowly, as if in meditation. Each statue is born to be offered, not kept a gift that dissolves in the wind, a sign of pure devotion. Here, papier-mâché becomes a sacred instrument, a bridge between the visible and the invisible. Among the scents of sandalwood and the distant sound of bells, paper transforms into spirituality, reminding us that even fragility can become eternal.

In Mexico

During Día de los Muertos, the streets are filled with calaveras small sculptures that celebrate memory, life, and rebirth. Those days, the air is perfumed with cempasúchil flowers, and altars tell stories of love for those who are no longer with us. Death is not feared but embraced as part of life a passage uniting the living and the dead in a great shared celebration. In this tradition, papier-mâché becomes an instrument of joy and continuity light yet resilient, just like memory itself.

In Venice

Papier-mâché becomes refinement and mystery. It is the soul of the Venetian Carnival, where masks symbols of beauty and freedom tell tales of celebration, art, and seduction. Thanks to its qualities, papier-mâché gave birth to the famous Venetian masks instruments of freedom and transformation, allowing one to conceal identity and, for a brief moment, erase social distinctions.

Everywhere, paper takes shape and everywhere, it changes temperament: sacred, festive, decorative, theatrical.

Lecce and the Birth of an Art

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, Lecce experienced a period of great dynamism and profound transformation its Baroque golden age. After centuries of Ottoman incursions and threats from the sea, the city fortified itself with new walls and bastions, becoming a bulwark against barbarian invasions.

When danger faded, the strength once devoted to defense turned into creative energy: thus began the golden age of Lecce’s Baroque.

The Counter-Reformation spurred the construction of churches and convents, while local architects and sculptors driven by deep devotion carved Lecce stone as if it were lace. In this climate of spiritual and artistic renewal, papier-mâché also found its truest expression: a humble material capable of transforming into works of extraordinary beauty, adorning altars and accompanying processions.

Lecce thus became not only a city to defend, but a city to admire protected by its walls and illuminated by the genius of its artisans.

Craftsmanship

Paper, glue, and plaster — modest materials that, in expert hands, become art.

The first to experiment with its magic were barbers themselves, who, between clients, modeled saints and nativity scenes in their shops. Their manual dexterity, trained in precision and patience, found in papier-mâché a new form of expression.

According to tradition, it was Mastro Pietro Surgente, known as Mesciu Pietru, who became the first great master of this art in Lecce. Active between the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Mesciu Pietru gave dignity and artistic form to a humble material, using it to create light, expressive, and profoundly human statues.

His works — made for churches, processions, and popular devotion — marked the beginning of a craft tradition that would make Lecce’s papier-mâché famous throughout Apulia.

Since then, Lecce has never ceased to shape paper as if it were stone: a tradition passed from hand to hand, still today uniting faith, creativity, and identity.

The Technique

Paper, glue, and plaster — modest materials, yet full of promise.

It all begins with the choice of paper, its tearing, soaking, and modeling on a mold. After drying comes painting, and finally varnishing, sealing the light within the material.

A slow, almost meditative process, where time becomes an ally.

Today, in my workshop, just steps from the Church of Santa Croce, I continue this tradition in my own way: by transforming papier-mâché into contemporary jewelry.

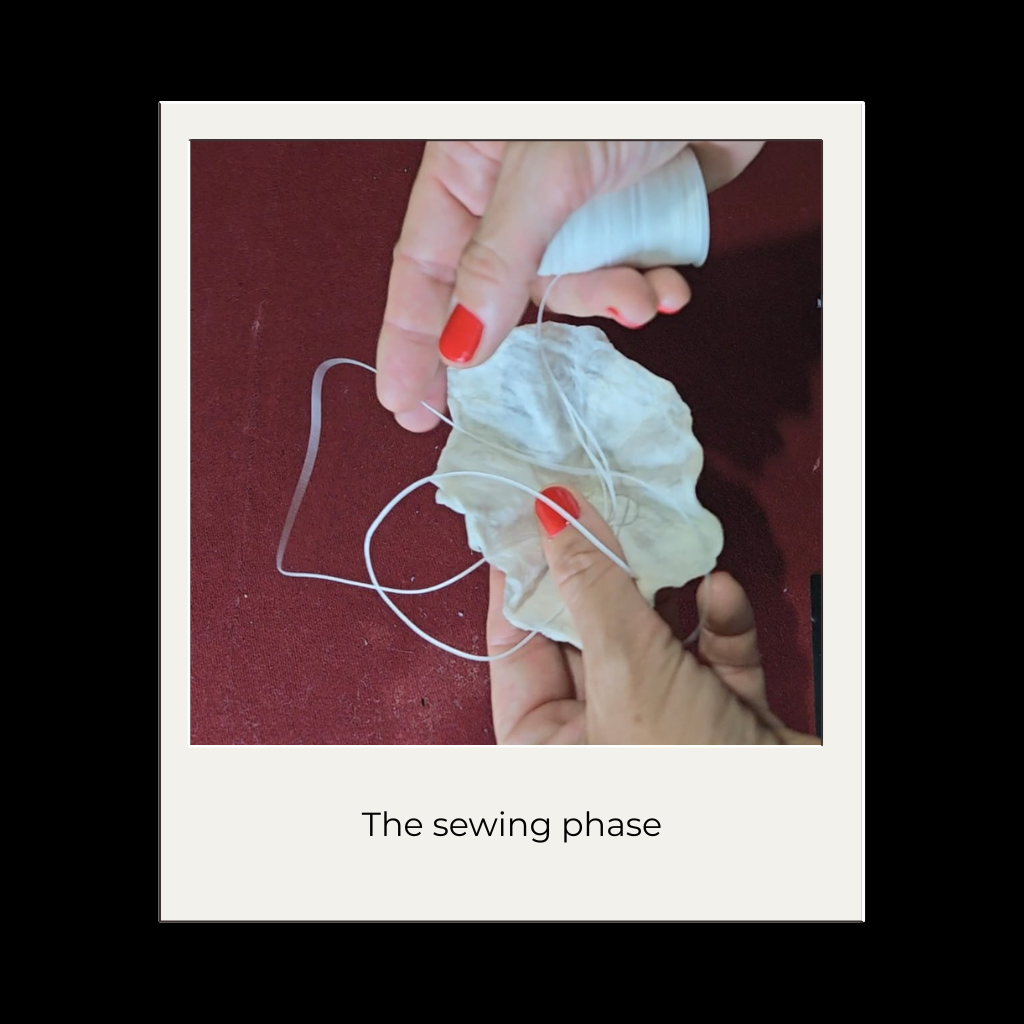

The Technique

1. Choosing the Paper

First, one must choose the type of paper to use — usually newspaper, kraft paper, or tissue paper.

2. Tearing

The paper is then torn into small pieces.

3. Soaking

The pieces are soaked in water to soften them.

4. Shaping

The softened paper pieces are applied to a mold and shaped.

5. Drying

Once the desired shape is achieved, the object is left to dry.

6. Painting

When dry, the object is painted and decorated according to the artisan’s inspiration.

7. Varnishing

Finally, to protect and give a beautiful finish to the object, a layer of varnish is applied.

Timeframe

About two weeks: the timeframe may vary depending on the complexity of the piece.

Each creation bears the trace of the gesture, the breath, and the South.

Nothing is fixed — everything is alive, like the material itself.